Beyond the Lottery Ticket: Multiple Winning Subnetworks in Pretrained LLMs

Preliminary evidence that random parameter selection can match full parameter RL finetuning.

Introduction

Reinforcement learning fine-tuning is a new axis of scale for

increased performance of Large Language Models (LLMs), with labs

scaling compute for RL to levels on par with pretraining. Recent works

have also attempted to shed light on the how and why RL really works

Important to this report, Mukherjee et al. (2025)

In this report, we present preliminary findings showing that random parameter selection can match full fine-tuning performance when training only ~1% of parameters. This suggests pretrained models may contain not just one winning ticket but potentially many and we are calling this the Multiple Ticket Hypothesis.

This report details on-going work on a small scale and the main reason

for sharing is that we think the temporary findings warrants

discussion and are interesting enough to be shared with the wider

community.

tl,dr of results

- Random parameter selection at 99% sparsity can match full parameter fine-tuning performance. This suggests pretrained models contain multiple viable subnetworks (the "Multiple Ticket Hypothesis").

- Fisher Information masks also work, validating parameter importance identification methods, but surprisingly offer no clear advantage over random selection.

- Different mask types require different optimal learning rates.

Background

Notation

Let $\theta$ denote the parameters of an LLM. We use $\theta^{(t)}$ to

represent the model parameters at training step $t$, with

$\theta^{(0)}$ denoting the initial pretrained model weights and

$\theta_i$ to denote the i-th parameter.

During an RLVR run, gradients at step t, $g^{(t)}$, are computed via

backpropagation, $$g^{(t)} = \nabla_\theta

J_{\text{GRPO}}(\theta^{(t)})$$

General Experimental Setup

In this report, all experiments are carried out on Qwen2.5-0.5B-Instruct. We trained via GRPO on Kalomaze's Alphabetsort environment. We also use AdamW optimizer for all RLVR runs. This work was also built on Prime-Intellect's RL training library.

Evaluation: For evaluation, we also use the same Alphabetsort env, selecting 512 samples, seeded to 2001.

Extracting sparse subnetworks

Our initial intuition:

Imagine a pretrained LLM with only 2 parameters, p1 and p2. If only

one parameter is changed at the end of a training phase with some

optimization function $\phi$, say p1, it must mean that p1 is more

important than p2 at satisfying $\phi$ is on the training set.

The question now is, how do we identify which parameters are most

important for some training data D?

Fisher Mask Works

To identify which parameters are most important for a given task, we

follow the approach laid out by Kirkpatrick et. al.,

We approximate the Fisher matrix, $F$

In practise, we sample a large batch of data, run a forward pass, a

backward pass and $$F_i = \theta_i.\text{grad}^2$$

We can then take the top x% of parameters in $F$, set

these to True and all else to False and thus

creating a binary mask $\text{MASK}_t \in \{0, 1\}^N$ over all

parameters.

Training with mask

During training with a mask, we modify the gradient update step to only affect the masked parameters: $$\tilde{g}^{(t)} = g^{(t)} \odot \text{MASK}^{(t)}$$ $$\theta^{(t+1)} = \theta^{(t)} - \eta_t \cdot \mathcal{U}(\tilde{g}^{(t)}, \theta^{(t)})$$ where $\odot$ denotes element-wise multiplication, $\eta_t$ is the learning rate at step $t$, and $\mathcal{U}$ represents the optimizer's update rule (e.g., AdamW). This ensures that only the selected subnetwork is updated while the full model is still used for forward passes.

In practise and for efficiency gains, we simply store the optimizer states for the subnetwork only.

Results

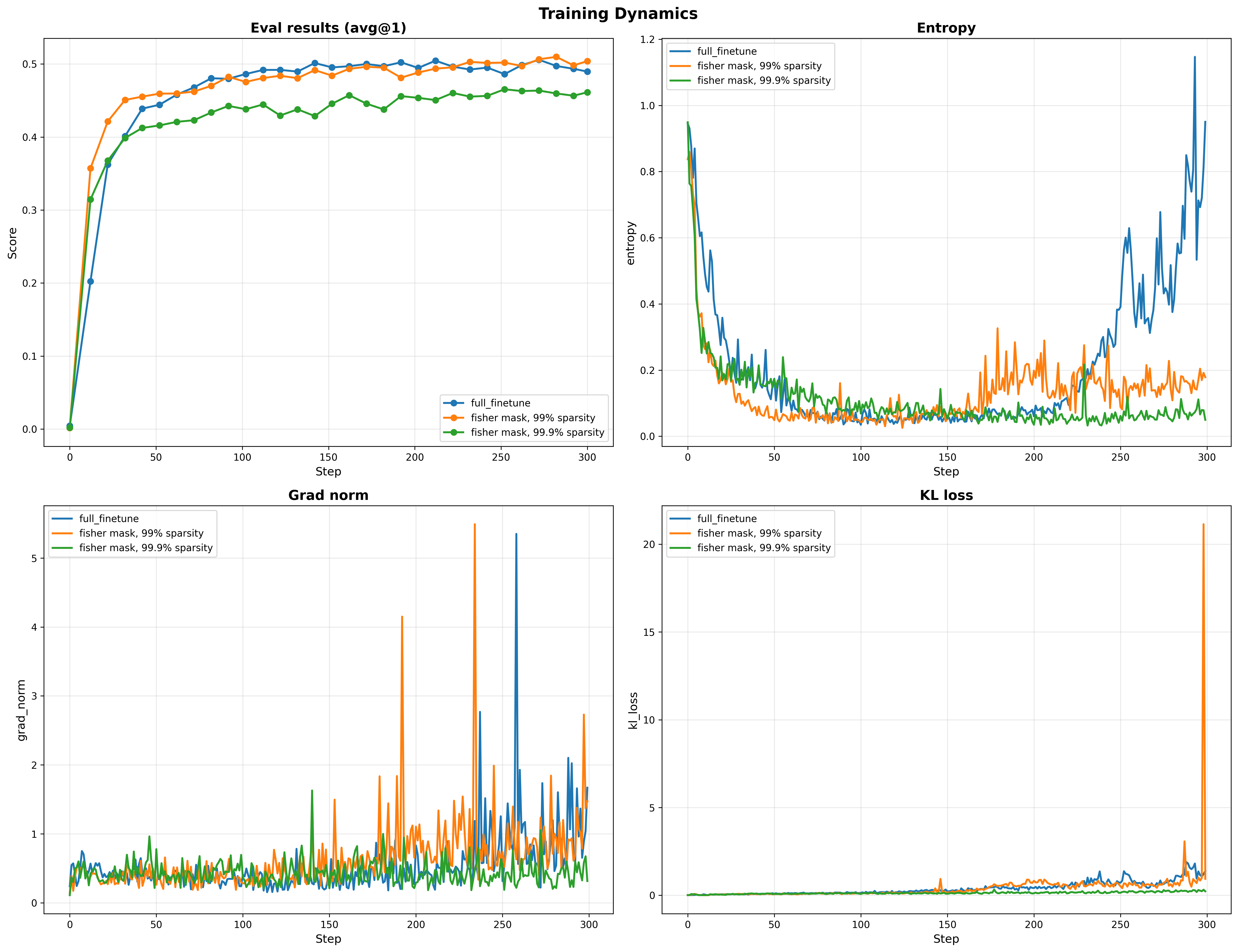

We approximate $F$ using a batch of 1024 samples. We then created two masks, one at 99% sparsity i.e 4,940,328 / 494M parameters and another at 99.9% sparsity i.e 494,032 / 494M parameters. We compare the eval results, as well as the training dynamics in Figure 1

We use a learning rate of $10^{-6}$ for the full finetuning run, $5 \cdot 10^{-6}$ for the 99% fisher mask and $10^{-5}$ for the 99.9% fisher mask run.

This confirms our initial hypothesis that indeed, parameter-importance identification (with Fisher info matrix) might be a way to pickout which subnetworks allow us get comparable levels of performance with the full finetuning.

The Surprise: Random Masks Also Work

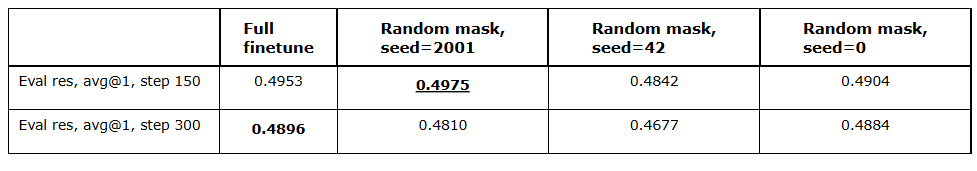

Having validated the initial intuition, we wanted to establish a baseline for comparison and investigated random parameter selection.We generated random masks at 99% sparsity by uniform sampling parameters to update.

Generating Random Masks

The implementation is pretty straightforward. We seed a random number

generator and select (100 - x)% of parameters uniformly

at random, to achieve x% sparsity.

We used three different seeds,

0, 2001 and 42 to get different

masks and ran an RL run with these random masks. The results in

Figure 2 are at $10^{-4}$, $5 \cdot

10^{-5}$ and $5 \cdot 10^{-5}$ respectively.

rng = np.random.default_rng(seed=42)

for name, param in model.state_dict().items():

if param is None:

mask_dict[name] = None

continue

temp_tensor = torch.zeros_like(param, dtype=torch.bool)

num_to_generate = int(param.numel() * keep_ratio)

indices = rng.choice(param.numel(), size=num_to_generate, replace=False)

temp_tensor.view(-1)[indices] = True

active += num_to_generate

mask_dict[name] = temp_tensor

Surprising Results

Figure 2 surprisingly shows that random parameter selection can match full fine-tuning performance. This finding challenges our initial assumption that some sophisticated parameter identification method would be necessary.

The learning rate puzzle

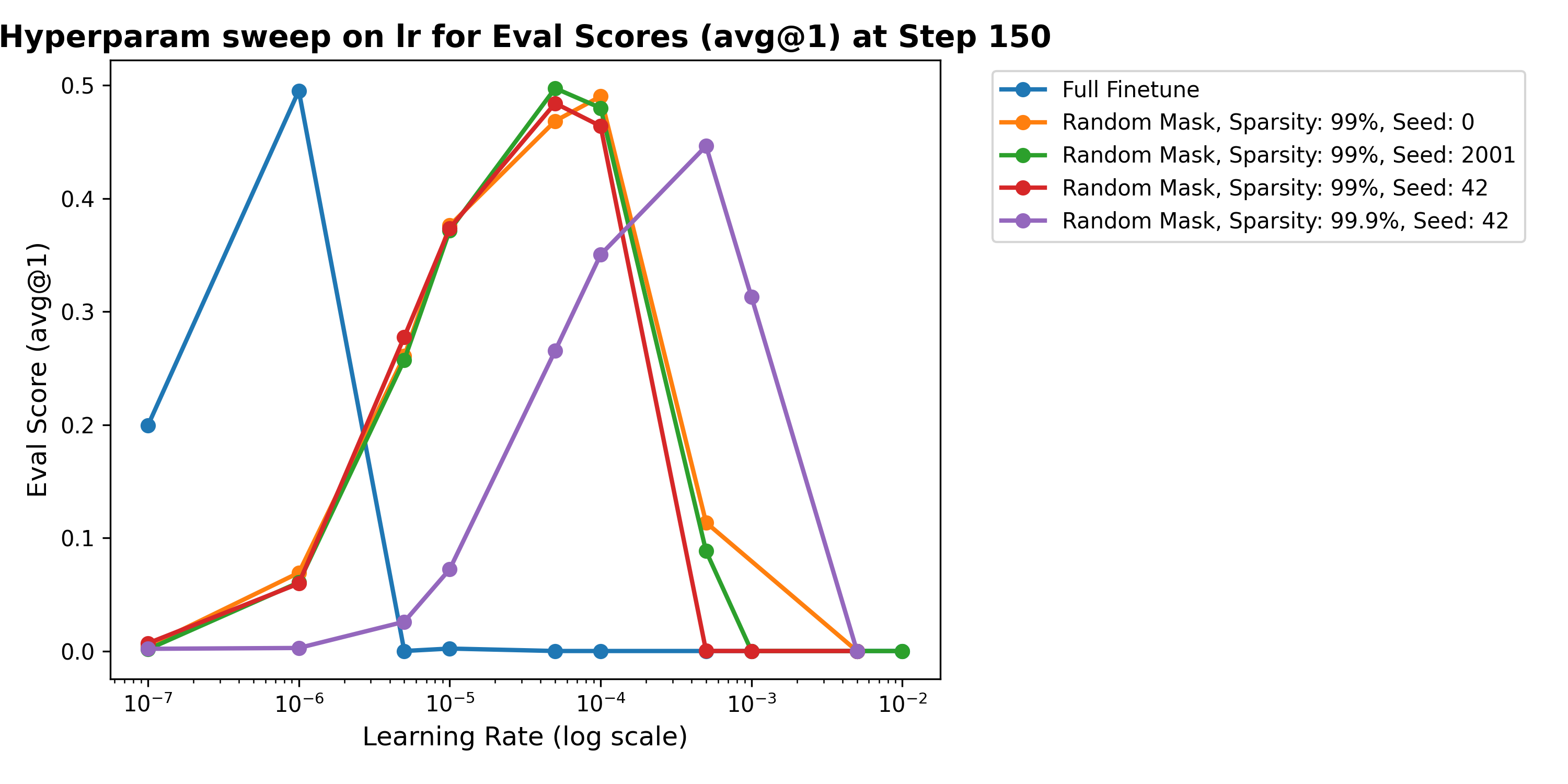

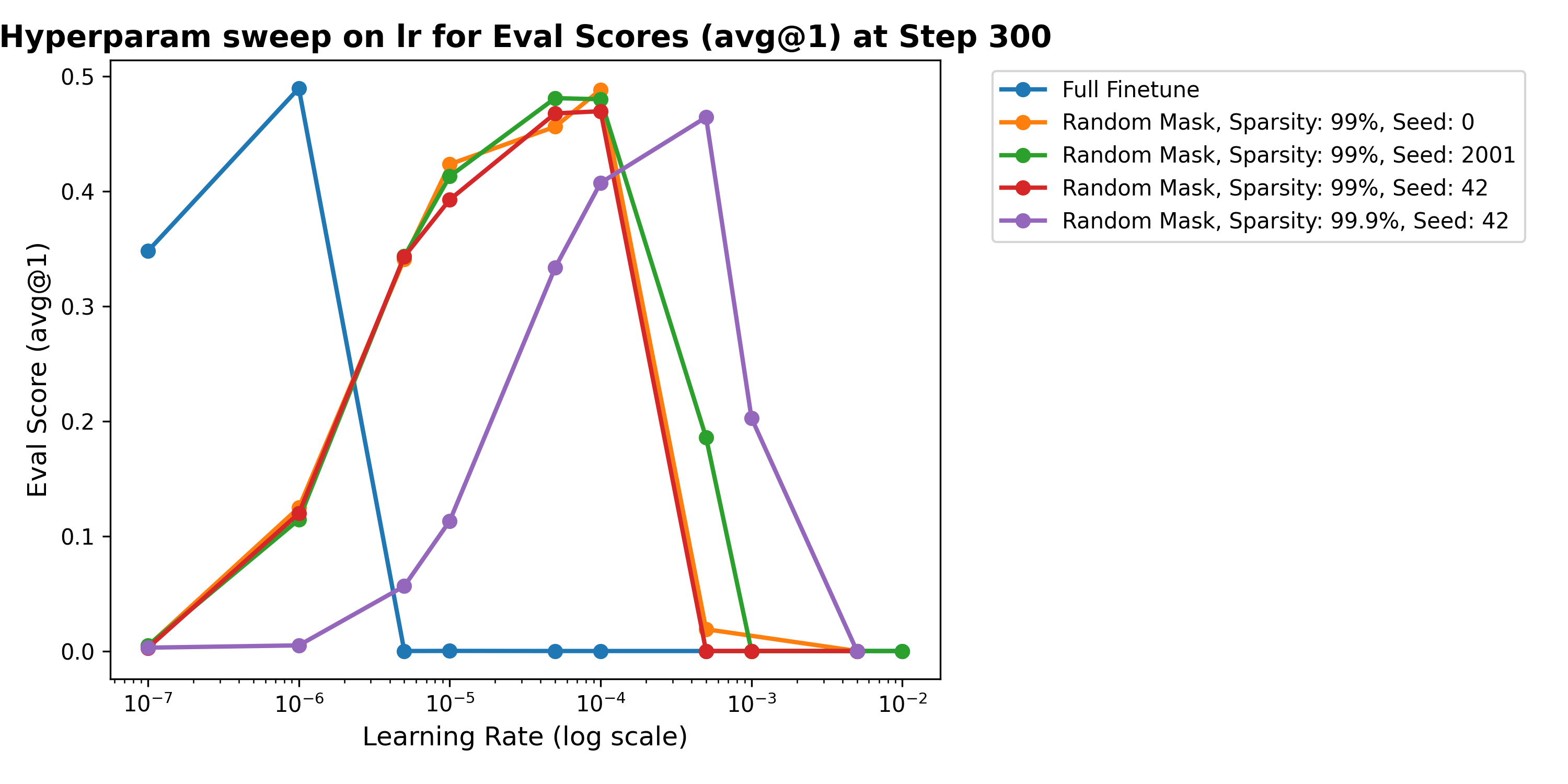

The key to making random masks and even the fisher mask work is

finding the right learning rate. We swept over multiple learning rates

for the random masks at 99% sparsity

Random masks perform best at higher lr, compared to full finetuning (and fisher masks). This isn't dissimilar to Thinkymachine's work on lora.

Why Different Learning Rates?

We hypothesize that this learning rate difference paints interesting pictures about the objective we are optimizing for and the training dynamics, with respect to the parameters of the model. Some of our hypotheses are:

- Fisher masks identify parameters already near optima: The Fisher Information Matrix identifies parameters with high curvature which could be interpreted to be that those parameters are sensitive to changes. These parameters may already be close to their optimal values for the task, requiring only small adjustments (hence lower learning rates).

- Random masks require more exploration or wiggling around: Random parameters are likely further from their optimal values on average, requiring larger updates to find good solutions (hence higher learning rates).

- Different regions of the loss landscape: Fisher masks may operate in high-curvature regions where large steps cause instability, while random masks may, on average, be in a region that appears flat and large steps are relatively safer.

Do Different Masks Select the Same Parameters?

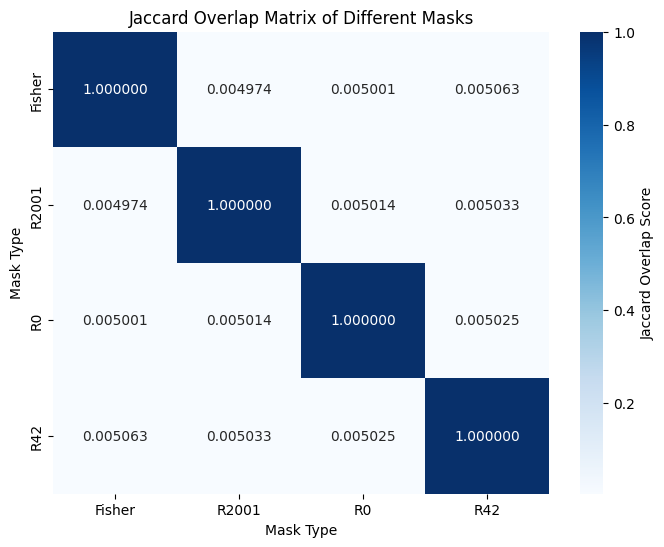

A natural question: are the random masks accidentally selecting the same parameters that Fisher masks identify? To answer this, we compute the Jaccard overlap between different masks, defined as $$ J(A, B) = \frac{|A \cap B|}{|A \cup B|} $$

The Jaccard overlap between the random masks and the Fisher mask, as shown in Fig. 5 is low, about 0.5% on average. This means that the random masks and Fisher mask select almost completely different parameters, yet achieve comparable performance to full fine-tuning.

Implications: The Multiple Ticket Hypothesis

These results suggest that LLMs appear to contain multiple viable sparse subnetworks that could be optimized on some task, not just one, for the Alphabet-sort task.

The Lottery Ticket Hypothesis (Frankle & Carbin, 2019)

Our findings extend the original LTH to the MTH:

For sufficiently over-parameterized pretrained models, there may

not be just one winning ticket, but potentially

many winning tickets — so many that even random selection

is likely to find one

i.e

You can just do things select random parameters and

train.

This explains why Fisher Information masks offer no clear advantage over random selection: Both methods (random masks and fisher masks) simply need to select some viable subnetwork and with appropriate hyperparameter tuning, they would succeed.

Caveats and Questions

These are preliminary results on a small model (Qwen2.5-0.5B) and simple task (alphabet-sort). More questions and ideas to investigate reveal themselves:

-

Does this phenomenon hold for larger models and different (harder)

tasks like math, code gen, logical reasoning (or any task that we

might want to make the model good at with RLVR)?

We suspect it would. It should also be straightforward to investigate this and it would be pleasantly surprising if it doesnt hold. -

It would seem logical that the parameters being repurposed for task

A under a random mask training might be close to optimal for another

task B. How does this random mask training affects the RLVR's

ability to reduce catastrophic forgetting (compared to SFT) on some

other task it has been trained on?

We're inclined to think that it would in some non-trivial way lead to poorer performance on some other previously trained-on task B, but what sort of task B? -

Some experiments (not recorded here) on even more extreme sparsity

level like 99.9% and 99.95% do not match the full performance. At

99.9% the max across steps was about 46% and even less for 99.95%.

What's the threshold for the number of parameters here?

It's not obvious that more params will equal more performance for the simple reason that using all the params is capped at some level. But at what threshold do we start getting comparable performances? -

On training dynamics, we also observe different convergence rates.

From preliminary experiments, higher learning rates converge faster,

at smaller sparsities, but they also become unstable more frequently

than other runs as well.

The question to investigate here isn't clearly formulated here, but it was still an interesting observation nonetheless -

Do random masks transfer across tasks, or are they task-specific?

We don't think they are task specific, but we don't also think that the same mask would behave the same across the different training tasks. - Why exactly do different masks require different optimal learning rates? How do we reason across this in relation to optimization theory specifically?

Answering these questions requires significantly more compute than we currently have access to. If you're interested in collaborating, mentoring or sponsoring compute, please reach out!!

Acknowledgements

- I am super grateful to Daniel and Andreas for sponsoring compute for the initial experiments as well as asking really insightful questions.

- PrimeIntellect also cooked with the prime-rl library. It was pleasant to hack around.

Citation

If you find this work useful, please cite:

@misc{adewuyi2025lottery,

author = {Adewuyi, Israel},

title = {Beyond the Lottery Ticket: Multiple Winning Subnetworks in Pretrained LLMs},

year = {2025},

month = {December},

url = {https://israel-adewuyi.github.io/blog/2025/slim-peft/},

note = {Blog post}

}